“…there are no grades until students turn 15, no timetables and no lecture-style instructions. The pupils decide which subjects they want to study for each lesson and when they want to take an exam (Source).” This is how The Guardian showcased a forward looking school in the heart of Berlin, Germany. The “Evangelische Schule Berlin Zentrum (ESBZ) is led by Margret Rasfeld – the probably most prominent principle in Germany. Under the leadership the school has grown in reputation and shown how a school can be organized radically different.

Rasfeld’s book – EduAction – describes the school in detail, but it has not been translated into English. Therefore, I’ve decided to give you a deeper look at what is being done at one of the most forward thinking schools in Germany.

The ESZB is a “Gemeinschaftsschule” (literally community school). These type of schools are fairly new to the German education landscape and they offer a more inclusive school form. Germany had ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities guidelines back in 2009 and set itself the goal of ensuring that every student – including students with special education needs – can attend regular schools if they like (Source). The Gemeinschaftsschule seeks to improve upward social mobility and achieve better integration of migrant children into society. That means there are no admission requirements and it is prohibited to separate students based on their abilities. I’ve written a blog post about the German education system, which you can find here.

I am fascinated by the school because of how it helps students develop. I don’t necessarily mean their academic skills, although they can be quite impressive. I am rather referring to the focus on developing character strengths, building deep relationships and building a solid moral compass in each student’s heart. Through their experiences at the ESBZ the students appear to have grown in confidence, self-efficacy, engagement and compassion. That should become obvious over the next few paragraphs.

In this post we’ll be looking at a timetable of an ESBZ student and go through the different “lessons” listed in it. We’ll also address the question of how well students are doing academically and they are being assessed.

The Timetable

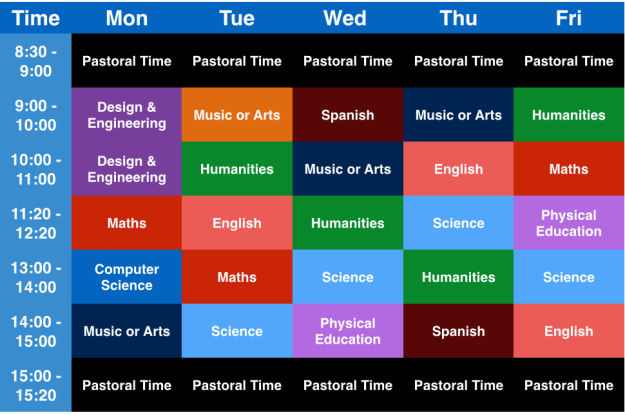

The timetable below is from a 7th grader at a London secondary school. There are 25 lessons per week + 5 hours of pastoral time spread across every morning and afternoon of the week. All of these lessons are mandatory and the curriculum is fixed.

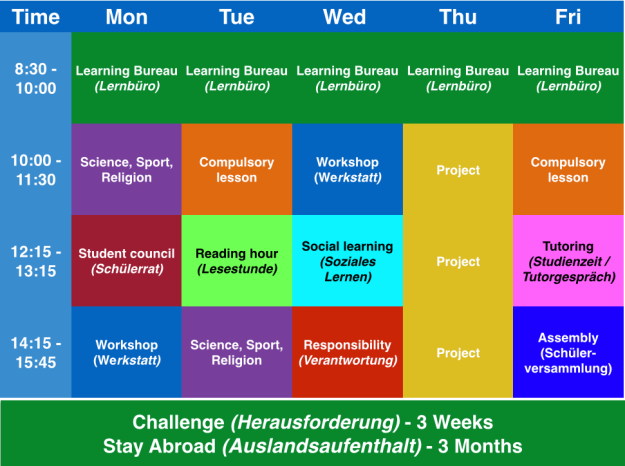

Below is the timetable of a typical 7th or 8th grader at the ESBZ. Although the lessons are fixed, the content is selected by the students. There are obviously certain tropics that all students need to cover, but aside from these it is all driven by students. Finally, the majority of the lessons are something you would not be able to find at a regular school.

Let’s go through each of these “modules” and see how they work:

Learning Bureau (Lernbüro)

Every morning, students spend 1.5 hours freely choosing the subject they want to study (German, English, Mathematics, Geography or History). As shown on the picture, worksheets are stored on bookshelves and sorted by topic. Students can choose any of these worksheets and get on with their learning.

Students are grouped into horizontal sets of 80 students that are composed of 7-9th graders. Teachers do not instruct, but act as Lernbegleiter (i.e. teaching assistants, mentors) who are viewed by students as the last resort in case their fellow students were not able to help them.

This arrangement leads to some interesting dynamics. First, giving students freedom over the subject and topic they want to spend time on gives them a feeling of control and agency, which is essential for human beings to feel content (see Daniel Pink’s “Drive“). Second, grouping students across year groups leads to more student-student learning. 9th graders can help 7th graders with their geometry work and refresh their own knowledge in the process. We know from memory research that relearning a topic after some forgetting has set in is a powerful way to consolidate memories as long-term memories. I would call this kind of social learning “quizzes in disguise”. Third, since teachers are not busy teaching they can focus on individual students who require more guidance.

Workshop (Werkstatt)

Students attend the Werkstatt (workshop) twice a week. In it, “7th graders get to choose a topic that matches their interests and abilities”. Here are some examples:

- The “Let’s go Shopping – Fair Consumption” course allows interested students to learn about how consumption impacts the environment and how to minimize it.

- A group of 10 girls formed “The Big Sisters” club where they visit a refugee home on a weekly basis and play with the kids that have recently fled to Germany from war stricken areas.

- A group of students are working on a music video with the help of a film production company.

- A father donated an old jolly boat, which the students fully restored in their woodworking area.

Just like the learning bureau, the workshop is student-led. The wide range of offers and strong practical elements makes it possible for all students to find something they might like. It challenges them to delve deep into a project and experience their own self-efficacy.

Social Learning and Student Council (Soziales Lernen and Klassenrat)

It is one of the core missions of German schools to educate students in their democratic thinking. Ideally, students leave the school being outspoken, responsible and socially active members of society. Just like other schools, students at the ESBZ attend classes in citizenship (Soziales Lernen) in which they discuss socially relevant topics. Students learn to develop their views and opinions and how to lead a proper discourse with others.

On top of these theoretical classes students are given 1 hour every week to run the Klassenrat (pupil’s council). In that hour, students deal with school-related topics such as mobbing incidents, the arrival and integration of new students or changes in the timetable. They also discuss their own projects such as organizing a school trip or redecorating their classroom. The whole lesson is student-led – from the contents to the decisions that are made. The teacher sits in the circle, rarely intervenes and may even have to leave the classroom if the students require more privacy (e.g. electing a teacher to be their mentor).

Topics are not only dealt with on a theoretical level, but they are also applied in a practical manner within the school context. Once more, students are given control over their daily lives, which means they have to take up responsibility. And through long discussions they learn from others’ point of views and how to have a discussion based on good arguments.

The Tutoring System

In case you were wondering how the teachers make sure that students are not falling off the rails – the tutoring system is the answer you’ve been looking for. Every student is assigned a teacher who acts as their tutor. The tutor is the student’s first point of contact and who keeps an overview of their progress in all subjects. They meet once a week to review the current and to plan the upcoming week. Students document their progress in a log book / planner that they have to bring to the meetings.

The big advantage of this approach is that students get a much more differentiated feedback on their progress and future targets. Students can better focus on their own progress instead of comparing themselves to others since everyone is doing something slightly different. Finally, since the students have a say in the planning process for the upcoming week, they can help set targets that are challenging, but realistic. The feeling of being confronted with attainable goals is crucial for their motivation. Too often have I seen students who have shut down because the lesson is going over their heads. This may in turn lead to self-doubt and a tendency to avoid challenges.

Projects

Over the course of the academic year, students need to complete 3 projects. Each project spans approximately 3 months. Every Thursday students are given 6 hours to work on their project. The topic can be anything from an in depth look at the French revolution to building a vegetable garden. Students are allowed to leave school during this time. They may want to talk to a historian about the French revolution or visit a local gardener to learn more about gardening. Teachers serve as mentors who step in when things become too challenging or go the wrong way. Their final work is presented in front of the school upon completion. It’s a bonus if the project has a social impact.

Students say they enjoy delving deep into a topic. School curricula are usually so crammed that every topic can only be studied superficially. I think that giving students so much time to work on a big project shows them just how complex things can be. It allows them to think in bigger terms.

School Assembly (Schülerversammlung)

“A school that does not know how to praise the week has not lived the week.” That’s what Rasfeld has to say about the value of praise. This school’s assembly is different from other schools in that teachers and students can come up on stage and highlight a special achievement by a teacher or fellow student. Praise can be given for small things such as “Mathilda helped me with my algebra today.” It may not be a grand thing in the large scheme of things, but for Mathilda, being praised in front of 400 students and teachers for something she has done is something quite the confidence boost. Standing on stage in front of 400 people can also be quite the challenge!

Giving praise so freely allows for students and teachers to express what matters to them. This in turn helps define what is being valued within the community. Over time, students internalize these values and carry them into their lives during and after they have left school.

I think it is needless to say at this point, but the assemblies are organized by the students.

Responsibility (Verantwortung)

According to the German Federal Agency for Civic Education the engagement within civil society has steadily decreased since 1999. That is a very frightening development since a democratic society depends on a strong public spirit and a shared sense of responsibility. But responsibility is not learned through books and moral pleas. It is rather learned by taking up real responsibility. Hence, the ESZB offers the course “Project Responsibility” in which 7th and 8th graders take up responsibility within their community for a year. Entrusting students with responsibility allows them to experience the positive effects that their own actions can have.

Ivi (15) describes how she helped primary school students plan and perform their own dance show (Source). The kids were anxiously awaiting Ivi’s arrival to the school and telling her she was the best dance teacher they ever had. These kinds of experiences can build tremendous self-confidence and give young people a sense of purpose they often don’t experience in a regular school.

The important aspect about this subject is that students feel needed and able to help (purpose and self-efficacy). Their achievements are showcased and celebrated during the school assemblies at the end of the academic year.

Challenge (Herausforderung)

During the the course “Project Challenge” students from 8-10th grade come up with a challenging task at the beginning of the year and work exclusively on it for 3 whole weeks. The project must take place off school premises. Each student is given 150 Euros of which they have to pay their rent, travel expenses and meals. 150 Euros is by far not enough money to cover those 3 weeks. Hence, students have to get creative. Here are some examples of what students did:

- A group of 4 girls (8th grade) went on a hiking trip through France. The train ticket to Paris cost them nearly all of their 150 Euro pocket money. They asked local residents if they could setup their tents in their gardens, which was particularly difficult due to language barriers. None of the girls spoke French and the English language is not widespread on the French countryside. Their parents thought they wouldn’t make it, but were – needless to say – incredibly proud and amazed that they had pulled through. The deep friendships that these girls formed by living through these hard times made them inseparable.

- A group of 5 girls organised a bike tour from Berlin to Greifswald (approx. 200 km). Although they were accompanied by an adult they were explicitly left to their own devices. During one evening they got lost because they were looking at their map completely wrong. The adult did not intervene. It is important for young people to work through mistakes on their own. They eventually found their way and successfully completed their bike trip.

- A group of 9 students joined their teacher on a 13-meter yacht from Greifswald to southern Sweden and Denmark. At one point they experienced wind forces of 7-8, which can be very frightening. Pulling through such intense emotional experiences can be highly rewarding and allows an individual to grow as a person. “When you’ve lived through such a tough experience for 3 weeks, life seems much easier afterwards” (Nicolas, 11th grade).

- 9 boys decided to spend their 3 weeks practicing their music instruments for 8 hours per day in an small village on the countryside.They were accompanied by their music teacher who helped them progress. “After having spent 3 weeks practicing with the same people you know each person so well that you can talk about their strengths and weaknesses with ease. The boys went on to perform at their school and later at a congress in front of 1600 people. 9 encores were played that evening.

- Henriette worked on a farm in southern France for 3 weeks in exchange for free accommodation and meals. She did not speak any French. Needless to say, traveling alone to another country has given her a tremendous confidence boost.

- Loukie – an 8th grader – wrote a 300-page novel. He says he has learned to see through the eyes of his character, which has allowed him gain a deeper appreciation for the fact that humans beings differ in their views and opinions.

Staying abroad (3 months)

In their 11th grade students must spend 3 months abroad. They are free to choose the project they want to join as well as their destination. Here are some examples of what students did:

- Antonia worked on a tee plantation in Darjeeling, India.

- Agnes worked on a permaculture plantation in Argentina.

- Shana went to Colombia to work for the NGO Fundación Viracocha and to re-discover her Colombian roots.

- 4 students traveled to Yunnan, China to work on a reforestation project. They also managed to raise 7,500 Euros for the project.

- Ben decided to attend a high school in Vancouver, Canada to improve his English skills.

I am a strong believer in inter-cultural exchanges. I think it is the best way to foster tolerance and understanding around the globe. Experiencing how other people lead radically different lives from yours is an eye-opening experience. It allows you to contrast your own life to theirs, which can teach you a lot about yourself – the privileges and shortcomings you may have as well as how to think about things differently.

Assessment

Instead of having students sit the same exam at the same time, students at the ESZB are given the option of writing any exam whenever they feel ready. The advantage is that students can go into examinations knowing they prepared well. This also eliminates something quite toxic: comparing oneself with other students. The focus shifts away from comparison and towards self-improvement. The discussion starts to automatically revolve around what could have been done better rather than feeling bad about having done worse than other – something teachers struggle to achieve at regular schools.

Students do not receive numerical assessments (marks, grades) until 9th grade, which is when they start preparing for their Mittlere Schulabschluss (comparable to the GCSE). Prior to the 9th grade they are given written feedback on their progress, which is very similar to Montessori and Waldorf schools. Written feedback is more elaborate and multi-dimensional. The teacher can express positive and negative aspects at the same time, which is something grades cannot. Grades have one dimension – good or bad.

Why is this approach worth it?

Here is s a direct comparison of a more traditional school with the ESBZ:

|

Old system |

New system (ESBZ) |

|

Fragmented school day into lessons and subjects. |

Long daily sessions, projects that stretch over months, students are given a choice on what to learn next. |

| Spoon-fed, externally driven, assessed. | Practice independent learning skills, build on interests, strengthen self-confidence. |

| Measured up against each other in a competitive system of winners and losers | Emphasize the importance of the community, working together, caring for others |

| Theorize over abstract and hypothetical scenarios. |

Turn theory into practice, act in meaningful ways. |

Rasfeld realizes that a brighter future must begin with creating compassionate societies that care for one another and the planet as well as learn to handle the increasing complexity and disruptive changes on this day in age. The big transformation that Rasfeld envisions is very simple:

“Schools must have people at the core of all their actions.”

That means, teaching them how to build confidence, how to be compassionate human beings, how to be active citizens and carry responsibility for their society, and how to help solve global challenges such as the energy revolution or climate change.

We need more schools like this.

The principal – Margret Rasfeld – has radically restructured her school. … She got rid of standard 45-90 min lessons because they hinder project based work, which can often times take much longer than a lesson. …

Rasfeld talks of 3 columns the school focuses on:

- First column – learning to act – involves acquiring interdisciplinary competencies as well as experiencing self-efficacy.

- Second Column –

For example, the “Responsibility Project” requires 7th and 8th graders to spend 1 year serving their local community as an extracurricular activity. Students are given 2 hours out of their weekly school schedule to do this. The project culminates in a presentation of the work at the end of the school year where students are honoured for their work. These kinds of projects show students how real-life changes can be achieved through their own doing within their local community.

Experiencing ones own self-efficacy strengthens self-confidence. One way in which the ESBZ helps students experience their own self-efficacy is through the “Challenge Project”. 8th through 10th graders take up a challenge for 3 weeks. Most of the students get together in groups, but some venture out by themselves. Henriette spent 3 weeks on a farm in southern France although she didn’t speak any french. The family provided her with an accommodation and food in return for her work on the farm. Loukie – an 8th grader – wrote a 300-page novel during those 3 weeks. Unlike regular lessons where students are guided by their teacher, these girls were left to their own devices. Having successfully completed their challenge, these girls must have gained a lot of self-confidence. I don’t know of any 8th graders who wrote a 300-page novel, not because it is impossible, but because they never get the chance to try. The added value that students can gain from such projects is tremendous.

A more powerful illustration of how rewards can have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation came in 1976. Students were presented with 7 puzzles, which were ranked in order of difficulty. Some of the students were told that they would get a reward upon solving a puzzle (reward group) and some weren’t promised anything (no reward group). The results showed that students from the reward group chose significantly less difficult puzzles compared to the students from the no reward group (

A more powerful illustration of how rewards can have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation came in 1976. Students were presented with 7 puzzles, which were ranked in order of difficulty. Some of the students were told that they would get a reward upon solving a puzzle (reward group) and some weren’t promised anything (no reward group). The results showed that students from the reward group chose significantly less difficult puzzles compared to the students from the no reward group (

9 AM. Security guards line up along the corridor at a young offenders prison in the UK. They escort one inmate at a time to their respective classroom. I only carry my notepad and a pen – anything else including phones is strictly prohibited. The inmates are between 15 and 18 years old and wear grey sweatshirts and sweatpants. As they walk down the corridor they turn and shout, asking for my name – clearly not shy. The large majority of them committed thefts or robberies, but a handful are in for murder or rape. I don’t know who is in for what and some of my colleagues have chosen not to inquire. They say it changes your perception of the inmate in a negative way. Together with Maggie, an art teacher, I wait in the corridor until all inmates have entered. She unlocks the classroom door using one of the keys on her heavy keychain that she carries in a special pocket fixed around her belt. She locks the door behind us.

9 AM. Security guards line up along the corridor at a young offenders prison in the UK. They escort one inmate at a time to their respective classroom. I only carry my notepad and a pen – anything else including phones is strictly prohibited. The inmates are between 15 and 18 years old and wear grey sweatshirts and sweatpants. As they walk down the corridor they turn and shout, asking for my name – clearly not shy. The large majority of them committed thefts or robberies, but a handful are in for murder or rape. I don’t know who is in for what and some of my colleagues have chosen not to inquire. They say it changes your perception of the inmate in a negative way. Together with Maggie, an art teacher, I wait in the corridor until all inmates have entered. She unlocks the classroom door using one of the keys on her heavy keychain that she carries in a special pocket fixed around her belt. She locks the door behind us. I meet Andrei, a 16 year old who moved with his family from Rumania to the UK. Andrei is a Romani (‘Gypsy’). He was caught by the police robbing a corner store and was sentenced to half a year in prison. I am told that he could hardly speak English when he arrived three months ago, but he has come a long way since then. I find him arguing with his British inmates about whether the Volga is an actual river. In March he will be deported back to Rumania, where his father as well as his girlfriend are waiting for him. He is supposed to get married and expects to have children very soon. He wants to live in Germany some day. His mom took off along with his three sisters after she found out that he had smoked weed. I can see how is cheerful character recedes as he tells me that he may never see them again. It truly pains him. He promised himself never to smoke weed again and hopes to make things right with his mom in the future. Like most of the inmates Andrei regrets what he did. When I was asked about what the inmates were like I found myself saying over and over again: “They’re just kids who did something stupid.”

I meet Andrei, a 16 year old who moved with his family from Rumania to the UK. Andrei is a Romani (‘Gypsy’). He was caught by the police robbing a corner store and was sentenced to half a year in prison. I am told that he could hardly speak English when he arrived three months ago, but he has come a long way since then. I find him arguing with his British inmates about whether the Volga is an actual river. In March he will be deported back to Rumania, where his father as well as his girlfriend are waiting for him. He is supposed to get married and expects to have children very soon. He wants to live in Germany some day. His mom took off along with his three sisters after she found out that he had smoked weed. I can see how is cheerful character recedes as he tells me that he may never see them again. It truly pains him. He promised himself never to smoke weed again and hopes to make things right with his mom in the future. Like most of the inmates Andrei regrets what he did. When I was asked about what the inmates were like I found myself saying over and over again: “They’re just kids who did something stupid.” The plexiglas windows have steel bar reinforcements and the doors are locked by the teacher from the inside. In case of an emergency, the teacher can press a green button on the wall, which will summon security guards within 10-20 seconds. A lot can happen in 20 seconds, given you reach the green button. There have been cases of violence against teachers – it’s a very real job hazard. However, most of the violence occurs between the inmates. I saw security guards rushing past my classroom because a boy had thrown chairs at another boy. He had to get stitches. In one of my classes, one of my boys threw another over the table – supposedly play fighting. It’s understandable why teachers refrain from pushing the kids too much.

The plexiglas windows have steel bar reinforcements and the doors are locked by the teacher from the inside. In case of an emergency, the teacher can press a green button on the wall, which will summon security guards within 10-20 seconds. A lot can happen in 20 seconds, given you reach the green button. There have been cases of violence against teachers – it’s a very real job hazard. However, most of the violence occurs between the inmates. I saw security guards rushing past my classroom because a boy had thrown chairs at another boy. He had to get stitches. In one of my classes, one of my boys threw another over the table – supposedly play fighting. It’s understandable why teachers refrain from pushing the kids too much.

Imagine teaching students about ‘balance’. In biology, you could talk about how prey and predators form a stable environment, how the extinction of a predator would lead to an overpopulation of prey animals and how that would throw the ecosystem off balance. You could also talk about homeostasis and how organisms keep their internal environment within certain parameters. In chemistry, students can learn about balancing chemical reactions and in physics about the balance of forces that keep the electrons in their orbits as well as earth around the sun. Many school already have such methods in place, but the concept of ‘balance’ could be extended to non-scientific fields as well – political balance between nuclear powers during the cold war, balance within a human relationship.

Imagine teaching students about ‘balance’. In biology, you could talk about how prey and predators form a stable environment, how the extinction of a predator would lead to an overpopulation of prey animals and how that would throw the ecosystem off balance. You could also talk about homeostasis and how organisms keep their internal environment within certain parameters. In chemistry, students can learn about balancing chemical reactions and in physics about the balance of forces that keep the electrons in their orbits as well as earth around the sun. Many school already have such methods in place, but the concept of ‘balance’ could be extended to non-scientific fields as well – political balance between nuclear powers during the cold war, balance within a human relationship.