Should students be praised for for good work? Is questioning an effective teaching method? And what is formative evaluation? All of these examples are forms of feedback. Giving feedback is probably the most important activity a teacher can perform, the effects of which vary widely – from helpful to counter-productive. This post will take a look at the scientific evidence on how different kinds of feedback – (1) rewards/praise, (2) formative evaluation and (3) questioning – can affect students’ achievement as well as the flipped classroom approach as a way of giving feedback a more central role in school.

This is the first post in a series of posts that will cover the different chapters of Prof. Hattie’s book ‘Visible Learning’. Hattie’s research summarises about 50,000 studies involving 240 million students worldwide, which is probably by far the greatest scientific contribution to the field of learning sciences. Therefore, we will tackle his findings and their implications in the coming posts.

Meta-Analysis and Effect Sizes

As boring as it may be, we’ve got to lay some ground work in order to be able to fully appreciate Hattie’s findings! First off: It’s a meta-analysis, which is a way of summarizing multiple papers that looked into the same thing and making one large paper out of it. If the initial findings of the single studies still exist after being merged it strengthens the findings significantly. It tells you that the findings are robust across multiple research groups that used different participants. Hattie found 800 meta-analyses that covered 50,000 single studies and decided to summarise these into a ‘meta-meta-analysis’. His findings encompass about 80 million students world wide, which makes his research very robust and credible. You see now why his research is so important?!

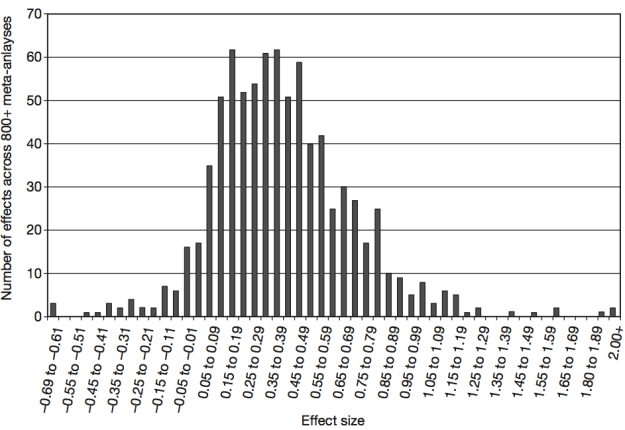

Hattie wanted to answer a single question – what is the effect of ‘X’ on students’ academic achievement. All of the findings will refer to the same outcome – students’ academic achievement. But the variable (X) could be swapped with anything that we might think could have an effect on students’ academic achievement (e.g. homework, kindergarten or feedback for that matter!). Check out the graph below. It shows all ‘X’s’ grouped into effect size ranges (x-axis). The effect size (d) is an expression for how big our variable is on students’ academic achievement. The bigger the value the more it contributes.

One thing that Hattie noticed is that nearly every intervention seems to have a positive effect on students! The average effect size is d = 0.4 and hardly anything we do to kids has a negative effect on their achievement. In fact, 95-97% of the things we do have a positive effect (source). Hence, if we want to know what differentiates good from great, we need to look at effect sizes above d = 0.4! Keep that in mind.

Theses effect sizes can also be translated back into more tangible forms. For example, an effect size of d = 1.0 can mean “…advancing children’s achievement by two to three years, improving the rate of learning by 50%,… When implementing a new program, an effect size of 1.0 would mean that, on average, students receiving that treatment would exceed 84% of students not receiving that treatment” (Source). That last bit in bold helps me understand effect sizes a bit better. It’s called the common language effect (CLE) and it basically turns ‘d = 1.0’ into ‘on average, 84 out of 100 students benefit from the treatment.’

Back to Feedback

I spent way too much time trying to understand what feedback actually is and apparently, John Hattie also had problems with it, as this quote shows: “When I was presenting these early results in Hong Kong, a questioner asked what was meant by feedback, and I have struggled to understand the concept of feedback ever since” (Source). Feedback is always something that follows instructions (teaching). If a student is taught a new method in math and given a set of practice examples, feedback would try to maximize the learning in whatever way is more suitable. Here is a more elaborate definition of feedback: “Feedback is information with which a learner can confirm, add to, overwrite, tune, or restructure information in memory, whether that information is domain knowledge, meta-cognitive knowledge, beliefs about self and tasks, or cognitive tactics and strategies” (Source).

Feedback is among the 10 largest effects that John Hattie found in his research. The effect size is d = 0.73 (based on 1,287 studies and 67,931 students). That means that 52 out of 100 students would show higher performance when given feedback vs. no feedback. That might not sound that great when you think of the other 48% of students for whom feedback apparently didn’t result in higher achievement, but d = 0.73 only refers to the average effect of feedback found across 1,287 studies – which all tested different kinds of feedback. Some lie far below d = 0.73 and some way above. I have picked the three most interesting types of feedback for us to look at: rewards/praise, formative evaluation and questioning.

Feedback Type 1 – Rewards and Praise

Who hasn’t been told at some point by their teacher that they’ll get a smiley stamp on their test if they do well in school? But what effects do such rewards have on kids’ learning behaviour? A 1999 meta-analysis looked at how tangible rewards affect students’ intrinsic motivation. Whether it’s about asking students to engage in a task (d = -0.4), asking students to finish a task (d = -0.36) and asking students to reach a certain performance level (d = -0.28) – every type of tangible reward reduced intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). That is at first sight rather surprising because you’d think that students would work harder to reach the goal. However, rewards completely change the way we learn in that our intrinsic motivation is shifted away from the act of learning and toward the reward. Rewards hijack students’ intrinsic motivation and learning becomes a means to an end. That doesn’t mean that rewards should never be given. Unexpected rewards can be a way of conveying that a task was done well and can motivate students to continue with their work. If unexpected rewards become too frequent, they become expected, making the reward the center of attention again (Deci et al., 1999).

Who hasn’t been told at some point by their teacher that they’ll get a smiley stamp on their test if they do well in school? But what effects do such rewards have on kids’ learning behaviour? A 1999 meta-analysis looked at how tangible rewards affect students’ intrinsic motivation. Whether it’s about asking students to engage in a task (d = -0.4), asking students to finish a task (d = -0.36) and asking students to reach a certain performance level (d = -0.28) – every type of tangible reward reduced intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). That is at first sight rather surprising because you’d think that students would work harder to reach the goal. However, rewards completely change the way we learn in that our intrinsic motivation is shifted away from the act of learning and toward the reward. Rewards hijack students’ intrinsic motivation and learning becomes a means to an end. That doesn’t mean that rewards should never be given. Unexpected rewards can be a way of conveying that a task was done well and can motivate students to continue with their work. If unexpected rewards become too frequent, they become expected, making the reward the center of attention again (Deci et al., 1999).

We often praise students in the hopes of motivating them to continue making an effort. A 1987 study from Israel placed students into 4 groups that got different types of feedback – comments, praise, grades and no feedback (control). Students could use the feedback to improve their performance. The results showed that the students who got the comments performed the best, but the students who were praised rated their performance significantly higher than all the other groups (Butler, 1987). We can draw two conclusions from this. (1) Praise is less effective in helping students perform than comments. (2) it gives the impression of performing well. That is actually quite a dangerous realization. However, if praise is given in form of positive feedback, thus combining feedback and praise, it can have a positive impact on students indeed (Deci et al., 1999).

We often praise students in the hopes of motivating them to continue making an effort. A 1987 study from Israel placed students into 4 groups that got different types of feedback – comments, praise, grades and no feedback (control). Students could use the feedback to improve their performance. The results showed that the students who got the comments performed the best, but the students who were praised rated their performance significantly higher than all the other groups (Butler, 1987). We can draw two conclusions from this. (1) Praise is less effective in helping students perform than comments. (2) it gives the impression of performing well. That is actually quite a dangerous realization. However, if praise is given in form of positive feedback, thus combining feedback and praise, it can have a positive impact on students indeed (Deci et al., 1999).

But praise has even more pitfalls. It works similar to rewards in that it is a positive feeling we get when others think highly of us. The problem with this is that students will want others to continue thinking highly of them. As a result, they often develop a high fear of failure and consequently stick to manageable assignments rather than pushing themselves with harder challenges.

Feedback Type 2 – Formative Evaluation

With an effect size of d = 0.9, formative evaluation just blows away most of the other effect sizes that Hattie found throughout his studies. Formative evaluation allows a teacher to keep track of the state of knowledge of her students in order to adjust her teaching style on the go. Formative evaluation stands in contrast to summative evaluation, which measures students’ performance at the end (e.g. final exam). The advantage of formative evaluation is that changes can be made early on to reach a desired goal more safely. A language teacher may ask her students to select the best thesis statement from a range of options. If all students select the right one she moves on. In contrast,”…if most of the students have chosen incorrectly, she might choose to review the work on thesis statements with the class. But if some have answered correctly while others have not, then she might initiate a class discussion. Moreover, because she knows which students chose which option, she can use this information to guide the discussion more effectively” (Source).

When the student’s needs are assessed attentively the teacher is able to give feedback to its fullest potential. Formative evaluation works best if the teacher listens carefully to the needs of the student. “It is the attention to the purposes of innovations, the willingness to seek negative evidence (i.e., seeking evidence on where students are not doing well) to improve the teaching innovation, the keenness to see the effects on all students, and the openness to new experiences that make the difference” (Source).

Feedback Type 3 – Questioning

Teachers spend about 35-50% of teaching time posing questions (van Lier, 1998). That makes questioning the most dominant teaching method, which is reason enough to talk about it. Hattie pooled together 7 meta-analyses and found an overall effect size of d = 0.46. That is slightly above the average of d = 0.4 that Hattie determined as the yardstick against which all effects should be compared to. The whole point of posing questions is to improve students’ understanding of things by getting them to think. Unlike instructions during which information is consumed rather passively, students are almost certainly thinking actively when a question has been asked.

Teachers spend about 35-50% of teaching time posing questions (van Lier, 1998). That makes questioning the most dominant teaching method, which is reason enough to talk about it. Hattie pooled together 7 meta-analyses and found an overall effect size of d = 0.46. That is slightly above the average of d = 0.4 that Hattie determined as the yardstick against which all effects should be compared to. The whole point of posing questions is to improve students’ understanding of things by getting them to think. Unlike instructions during which information is consumed rather passively, students are almost certainly thinking actively when a question has been asked.

Questions can be divided into low and high-level questions. 82% of all questions are of the low-level type and they typically ask students to recall facts or procedures (Cotton, 1989). Teachers still think that “… their role is to impart knowledge and information about a subject, and student learning is the acquisition of this information through processes of repetition, memorization, and recall: hence the need for much questioning to check that they have recalled this information” (Source). That is all well! The process of repetition is essential for memorization. But higher-level questions are also necessary for reaching deeper understanding. Socratic questioning is systematic and disciplined. For example, asking “why do you think that might be true?” would force students to clarify their own argument, while “what is the counter-argument?” would open them up to the possibility of other opinions. Consequently, the student may realize that their own perspective of things is not the truth, but rather only one way of looking at something.

Maximising Feedback – The Flipped Classroom Approach

Since feedback is so important for the performance of students, shouldn’t we try to optimize schools so that the power of feedback can develop its full potential? One way of doing it would be to ask students to learn the materials from online videos (e.g. Khan Academy) at home and do practice examples under the teacher’s supervision in school. With all of these wonderful free online resources, wouldn’t it make more sense if the teacher focused on giving feedback? This approach – now termed the flipped classroom approach – has been popularized lately. A recent article showcases the Clintondale High School in Michigan that was able to reduce the failure rate from 35% to 10%. College enrolment increased from 63% to 80% in only 2 years (Source). Those are quite impressive findings, but it remains to be seen whether the approach results in higher student achievement under scientific conditions. There is surprisingly very little work looking into this (Source), but is of high relevance, given the Clintondale High School success.

What has been found so far shows that “…student perceptions of the flipped classroom are somewhat mixed, but are generally positive overall. Students tend to prefer in-person lectures to video lectures, but prefer interactive classroom activities over lectures” (Source). I had talked about Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) in a previous post (here), which showed that also university students show much worse performance when in-person lectures are replaced with video lectures. Students complained about the lack of access to the teachers and reported feeling left alone with the tasks. So you see, the discussion regarding flipped classrooms is hardly over, but has rather just begun.

Summary

- John Hattie has done some marvellous work on what helps students reach higher levels of achievement in the classroom.

- Feedback (d = 0.73) is one of the largest effect sizes Hattie found and it is one of the most important activities a teacher can perform. There are some types of feedback that work and others that are counter-productive.

- Rewards and praise actually have negative effects on student achievement and reduce their intrinsic motivation.

- Formative evaluation (d = 0.9) is by far the greatest thing a teacher can do, but it only works well if the teacher is willing to listen carefully to what the student needs.

- Questioning (d = 0.46) is the most used teaching method with a moderate effect size. Both low and high-level questions are necessary to ensure learning of facts as well as deep understanding.

- The Flipped Classroom Approach is a powerful way of unleashing the power of feedback to a much larger degree than in traditional teaching approaches, but it has not been properly validated by scientific studies yet.

Feedback is powerful and I think it will become even more important as access to instructions is becoming more easy. A student may be able to listen to great lectures online and download wonderful education apps, but having a teacher that can help improve the learning process through feedback is essential. If done right, teachers can make students enjoy the learning process, maybe even for a lifetime.