What’s the big picture here? How many kids around the world are still out of school? What is the world community doing to change that? Is there progress and could we speed things up a little – let’s say, with the internet?

The Difference between Improving and Spreading Education

People are generally trying to do one of two things in education – improve it or spread it. Under improvement fall things like considering scientific findings regarding brain development and kids and adjusting the learning material accordingly. It also means to try out different concepts (e.g. Waldorf, Montessori, all-day schools or boarding schools – see previous post: Grades, What They Are and What They Measure) as well as introducing more technology into the classroom. These are the topics that are most commonly dealt with in developed countries where education is accessible to everyone. We talk about creating equal opportunities, because that is the next step in the development of our education systems that we have to figure out. However, many countries around the globe still struggle with providing universal access to education.

Spreading education is a completely different domain. You might be struggling with convincing a teacher to come twice a week to an isolated village to teach math, while improvers try to lobby for more equal opportunities for kids with different backgrounds. Today’s industrial nations once struggled with spreading education as well. When the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm I announced in 1717 the first mandatory school system there was no education infrastructure present. There were no school buildings and no teachers, but in 1740 Prussia had already constructed 1480 schools (source). That is a rate of 1 new school every 5-6 days over 23 years! Developments of course continued, but what you can see from this example is that it takes time to build an education infrastructure (see previous post: The Origins of Education).

Things can surely move much faster nowadays than in the 18th century. While the industrial revolution took more than a century to complete in Europe it is now being achieved at a fraction of that time in todays’ developing countries. I guess that pioneers always have it tougher because they cannot copy from others on how to do things in the best way and what pitfalls to rather avoid. Progress is all about trial and error. But when it comes to spreading education we can rely on prior experience. We know what is required to build education systems. There are countless NGOs, funds and volunteers who try to bring the number of kids without an education down. This mostly involves being on site, training or sending teachers, providing learning material and financial support for families. Some of these programs are really good and they achieve great things, but they seem a bit like a drop in the ocean when looking at education on a global scale.

Scalability – An Introduction

I want to take a little detour to talk about the concept of scalability. In the business world, scalability means to expand rapidly without dramatically increasing one’s costs [or effort] (Source). The graph shows how a scalable business can grow exponentially while the extra effort hardly required hardly increases. Take for example the McDonalds franchise system. If you have the necessary financial resources you can open your own McDonalds. All you have to do is stick to the McDonalds guidelines (e.g. how long the meat needs to be on the grill or what is generally on the menu) and pay branding/licensing fees . You would benefit from the brand and McDonalds spreads their brand and earns more money without moving a finger. There are many such examples, but the large majority of the most recent scalable businesses can be found on the internet. Any teenager who knows how to build a website can offer a service and cater customers across the globe. Take Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook, which he created single-handedly and which was used by 864 million people daily in September 2014 (source). Since the content is generated by the users, Facebook just has to make sure that their servers don’t crash to keep their service online.

I want to take a little detour to talk about the concept of scalability. In the business world, scalability means to expand rapidly without dramatically increasing one’s costs [or effort] (Source). The graph shows how a scalable business can grow exponentially while the extra effort hardly required hardly increases. Take for example the McDonalds franchise system. If you have the necessary financial resources you can open your own McDonalds. All you have to do is stick to the McDonalds guidelines (e.g. how long the meat needs to be on the grill or what is generally on the menu) and pay branding/licensing fees . You would benefit from the brand and McDonalds spreads their brand and earns more money without moving a finger. There are many such examples, but the large majority of the most recent scalable businesses can be found on the internet. Any teenager who knows how to build a website can offer a service and cater customers across the globe. Take Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook, which he created single-handedly and which was used by 864 million people daily in September 2014 (source). Since the content is generated by the users, Facebook just has to make sure that their servers don’t crash to keep their service online.

Before taking the concept of scalability into education let’s take a look at how we, as a species, are working together to spread education across the globe.

Universal Primary Education

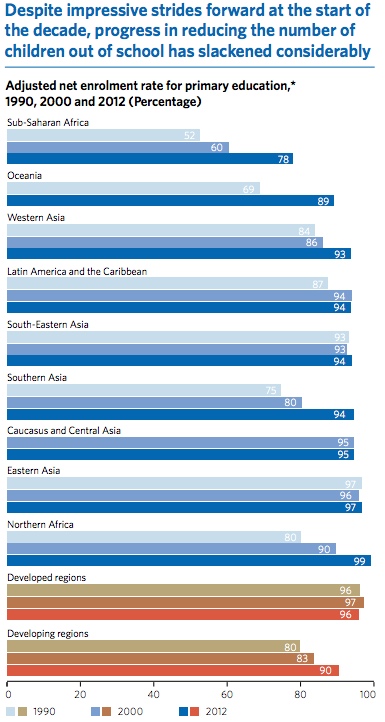

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (UN MDG) that were initiated by the UN Secretary Kofi Annan in 2000 set 8 ambitious goals that were targeted and had to be met by 2015. Large sums of money were annually allocated to low and middle income countries to help reach those goals. The second goal is about education. It reads that “…by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling achieving universal primary education until 2015” (Source). The UN defines primary education to be 6 years of basic schooling. The graph on the right is taken from the United Nations’ MDG Report 2014 (Source). You can see massive improvements between 1990 and 2012. Only Sub-Saharan Africa has not yet been able to bring primary education to at least 90% of its children, but major improvements have been observed there as well over the last decade. The gap is closing, but not at a fast enough rate. In 2012, there were still 58 million kids without primary education worldwide. That is 1 in 10 children out of school (Source). We are not moving at a fast enough pace to achieve this goal until 2015, which is why people have been looking for alternatives.

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (UN MDG) that were initiated by the UN Secretary Kofi Annan in 2000 set 8 ambitious goals that were targeted and had to be met by 2015. Large sums of money were annually allocated to low and middle income countries to help reach those goals. The second goal is about education. It reads that “…by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling achieving universal primary education until 2015” (Source). The UN defines primary education to be 6 years of basic schooling. The graph on the right is taken from the United Nations’ MDG Report 2014 (Source). You can see massive improvements between 1990 and 2012. Only Sub-Saharan Africa has not yet been able to bring primary education to at least 90% of its children, but major improvements have been observed there as well over the last decade. The gap is closing, but not at a fast enough rate. In 2012, there were still 58 million kids without primary education worldwide. That is 1 in 10 children out of school (Source). We are not moving at a fast enough pace to achieve this goal until 2015, which is why people have been looking for alternatives.

Scalability and Education

Scalability does not seem to be working in education, at least for now. The most prominent example of scaling education comes from higher education. In 2011, David Stavens and Mike Sokolsky – two roboticists from Stanford University – offered that students from around the globe could join their lecture on artificial intelligence for free on the web. They had initially expected no more than 2,000 students, but eventually 200,000 people had signed up (source). Since then, many such ‘Massive Open Online Courses’ (MOOCs) have emerged, the most famous websites that offer online courses are the MIT/Harvard non-profit company http://www.edx.org as well as the Stanford for-profit spin-offs Coursera and Udacity. Many have believed and still believe that companies such as Udacity are “…poised to potentially revolutionise education” (source). MOOCs deliver high quality lectures for free to anyone in the world with an internet connection. BUT “So far, most MOOCs have had dropout rates exceeding 90 percent” (Source). Udacity MOOCs have also been introduced at the San Jose State University to cut costs, but the student passing rate was alarmingly low: Elementary statistics (50.5%), College algebra (25.4%), Elementary Math (23.8%) (Source).

Why are online courses failing as a substitute for conventional courses? The documentary Ivory Tower argues that students were unhappy with the lack of feedback and lack of general interaction with the professors as indicated in the courses’ comment sections (Source). The importance of human interaction in learning has probably been underestimated quite a bit even in the realm of higher education where students are usually expected to work independently. Companies like Udacity may one day find a format that works, but it will surely be even more challenging to get young school kids to participate in online lectures. Education remains to a large degree non-scalable (linear).

Teachers are Essential

MOOCs require students to work very independently, which is a skill that kids from primary school do often not have. They heavily rely on the guidance of their teachers and parents. Just how important the teacher is for the success of a child is impressively demonstrated by John Hattie, Professor of Education and Director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Over the course of about 15 years he has aggregated the results of more than 50,000 studies on what works best in education (Source). The result: “…the best way to get higher achievement is to improve the level of interaction between pupils and their teachers” (Source). The student-teacher relationship has an effect size of d=0.72 on students’ success, which is quite impressive (the effect size measures the difference between the control group and the experimental group, with a d-value of 0.72 signifying a medium to large effect).

What Hinders the Spread of Education

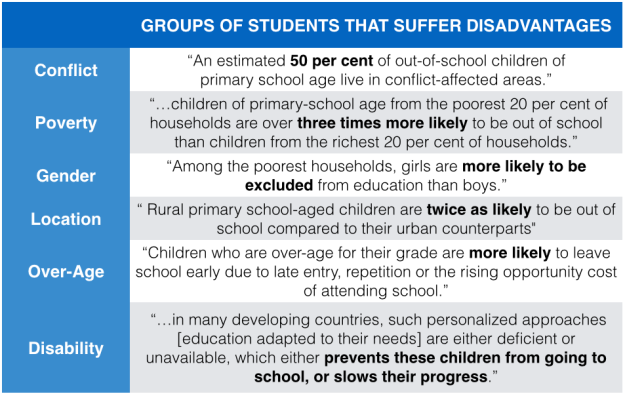

The UN MDG Report 2014 mentions 6 factors that put certain groups of kids at a higher risk of not receiving primary education. I have listed them in the table below.

What this table shows quite nicely is how multi-faceted and intertwined education is with society. Less primary education attendance is linked to politics (conflict-affected areas and rural areas), the economy (poverty) as well as culture (gender and disability inequality). Universal primary education can be achieved more easily if certain basic societal conditions are met. Wars need to stop, average incomes have to rise and the role of women and disabled within society has to change. It is obvious that the billions of dollars that the UN has made available to low and middle income countries to achieve universal primary education by 2015 cannot solve the problem of poverty and wars. These factors that clearly affect school attendance have to be dealt with by economics departments and politicians. However, the available money can be spent to battle some of the other factors. For example, building schools in rural areas would get more rural kids into school and offering special education programs for disabled students is also feasible.

The goal of reaching universal primary education has gotten into our reach and UN member state efforts have most likely contributed to it. There appears to be a clear correlation between UN aid and progress being made (Source). Money seems to help solve the education problem, but is enough money available? And are governments actually spending enough money to reach the MDG? It turns out, finding out how governments spend their money is not so easy. The NGO Government Spending Watch has – just 32 months before the MDG deadline – released a report on whether governments are spending sufficient money to reach each of these goals. 20% of total spending is estimated to be sufficient to reach the goal, but only 12 out of 51 countries that have not reached universal primary education yet are spending that amount.

The goal of reaching universal primary education has gotten into our reach and UN member state efforts have most likely contributed to it. There appears to be a clear correlation between UN aid and progress being made (Source). Money seems to help solve the education problem, but is enough money available? And are governments actually spending enough money to reach the MDG? It turns out, finding out how governments spend their money is not so easy. The NGO Government Spending Watch has – just 32 months before the MDG deadline – released a report on whether governments are spending sufficient money to reach each of these goals. 20% of total spending is estimated to be sufficient to reach the goal, but only 12 out of 51 countries that have not reached universal primary education yet are spending that amount.

The graph below shows a handful of selected countries and their spending on education. EFA stands for Education for All, which is a new standard that includes pre-school care and fighting adult illiteracy. The same report also states that “Education spending has risen slightly, but most countries have been reducing it as % of budget or GDP” (Source). In other words, the piece of the GDP pie that is allocated to education is becoming smaller. That does not necessarily mean that spending on education is decreasing because pies can grow in absolute size! But still, targets are not being met by the large majority of countries.

There appears to be insufficient money available to spend on education. The recent world economic crisis has caused an estimated $140 billion in revenue loss in poor countries. 40% of their extra spending was actually funded with borrowing money (Source). This drives countries into debt. How can countries be expected to keep investing in education if revenues are going down? Other sectors such as food and water security are obviously more important than education. This is probably where the money will and should go first. As a consequence, the international community needs to increase its total aid to help develop education systems. The OECD reports a $61.2 billion aid gap (for all MDG combined) that would have to be closed in order to reach targets (Source). Another final issue is that we do not know whether the UN aid is being spent on what it was initially meant for (corruption).

In Conclusion

Whether a kid can go to school very much depends on global factors such as the recent world economic crisis. But much of it is also luck. Being poor, a girl, living in a rural and/or conflict-affected area – these are all factors that reduce the chance of attending school. It is interesting to see how the spread of education goes hand in hand with other things we value: eradication of poverty and war and achieving equality. Due to the interconnectedness of these various topics we can work on one of these issues and solve others indirectly.

The MDG of achieving universal primary education by 2015 is a noble goal, but whether we reach similar goals in the future depends to a large extent on how much we are willing to help each other in terms of finances as well as how that money is ultimately being spent. Money does help and we need more of it because education is linear, not scalable. As long as there is no brilliant solution to change that we will have to raise our efforts.